Robert Greene (1558-1592), a writer who lived at the same time as Marlowe, is often described as “clearly envious of Marlowe” (Bevington and Rasmussen viii) and as one who “slavishly imitated” Marlowe (Ribner 162). In his preface to Perimedes the Blacksmith (1588), Greene complained about Christopher Marlowe and Tamburlaine in particular. Ironically, today, the text of Perimedes is not often studied; instead, it is Greene’s reference to Marlowe that continues to capture scholarly attention. Greene’s words are now remembered because they offer evidence about the date of Tamburlaine’s first performance; criticize Marlowe’s writing and morals; and perhaps reference a lost play.

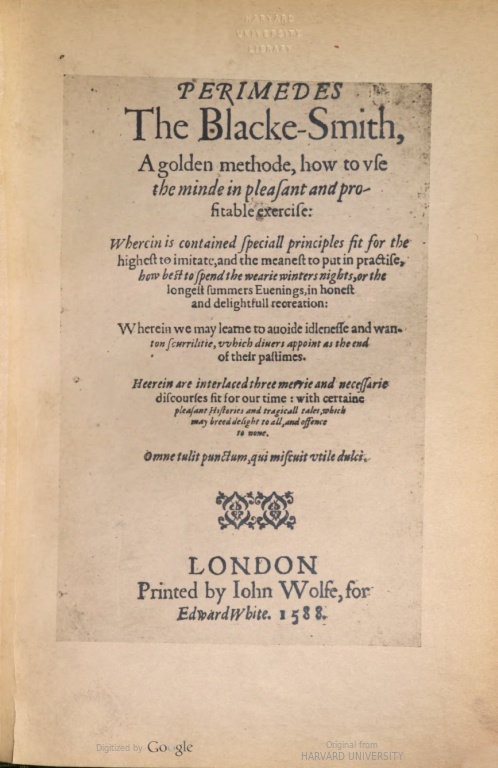

Perimedes the Blacksmith (1588) is a prose story about a husband and wife exchanging tales over three evenings. Perimedes is a 62-page quarto volume published in 1588 that exists in four known copies (ESTC); a digital transcription is available from EEBO-TCP (Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership). Parts 1 and 2 of Tamburlaine were first published, together, in 1590. Greene’s reference offers evidence of performance for Tamburlaine as early as 1588; scholars now accept a 1587 or 1588 date of composition.

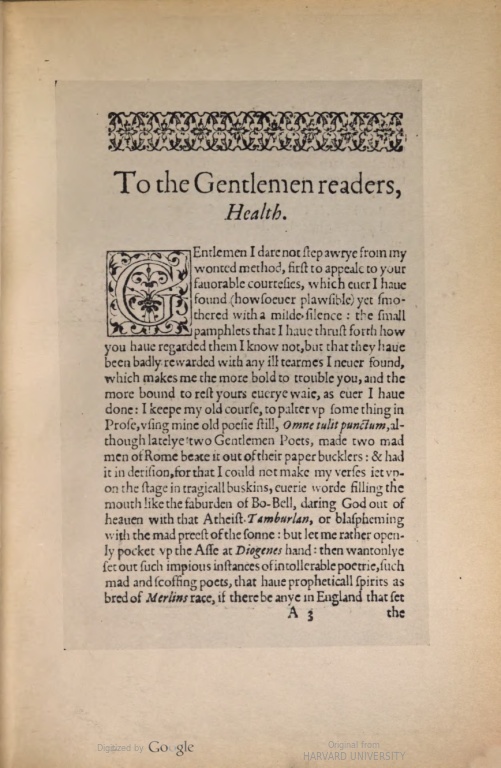

Greene’s prefatory letter “To the Gentlemen Readers, Health” (sig. A3-A3v) includes an extensive discussion of Marlowe:

lately two Gentlemen poets made two mad men of Rome beat it out of their paper bucklers: and had it in derision, for that I could not make my verses jet upon the stage in tragical buskins, every word filling the mouth like the faburden of Bo-Bell, daring God out of heaven with that Atheist Tamburlaine, or blaspheming with the mad priest of the sun.

The “paper bucklers” that Greene describes are prop shields, also perhaps referencing printed title pages (Martin 321). “Tragical buskins” are a style of boot worn by actors performing tragedies. In short, Greene grumbles about two poets who criticized him for not writing successful tragedies for the professional stage.

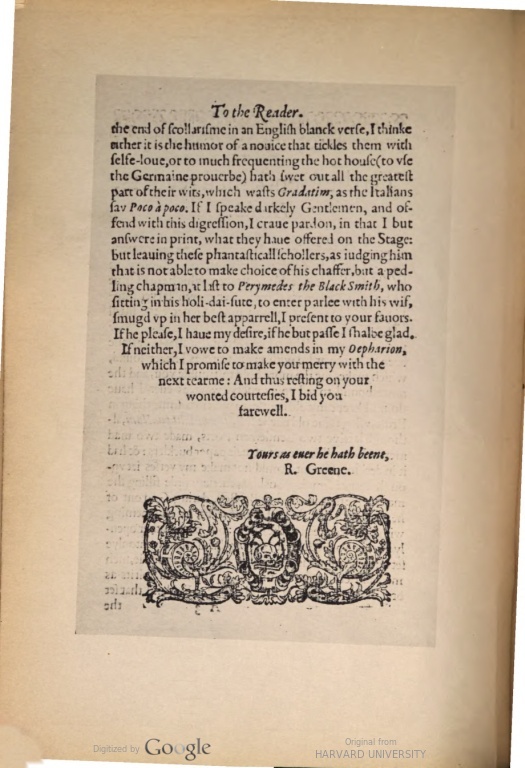

The two main points Greene raises to disparage his rival poets are their language and portrayals of atheism. Greene’s dismissive description of “every word filling the mouth like the faburden of Bo-Bell” is about poets using bombastic language (Bull 301; Syme 283); a “faburden” is a song and the “bow bells” are the bells of St. Mary-le-Bow that rang in Cheapside, London (Martin 321). Greene continues, lambasting “Such mad and scoffing poets that have poetical spirits, as bred of Merlin’s race, if there be any in England that set the end of scholarism in an English blank verse.” Tom Rutter points out that Marlowe’s name was sometimes spelled “Marlen” (110), making this attack even more personal. Marlowe was well known for popularizing blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter) on the English stage. Here, Greene criticizes Marlowe’s language for its affectation.

Greene’s second criticism of Marlowe is for “daring God out of heaven with that Atheist Tamburlaine.” This passage is often read in reference to Tamburlaine, Part 2, when Tamburlaine burns the Quran (Ide 269). Constance Kuriyama explains that by calling Tamburlaine an atheist, Greene was also “indirectly” accusing Marlowe himself of atheism (114). Arata Ide traces how Greene’s invective, “that Atheist Tamburlaine” came to be associated with “the urban legend of Marlowe the atheist” (272), showing how Greene positions himself as a moralist in contrast to Marlowe’s blasphemy. Marlowe’s possible atheism is one of the major received narratives about his life, whether or not it is true (on this, see Downie and Erne); his potentially unorthodox beliefs continue to generate fascination with his life and works. By yoking Marlowe to atheism, Greene’s words in Perimedes contribute to Marlovian myth-making.

Greene responded to Tamburlaine’s atheism by writing his own Ottoman heroical romance, Alphonsus, King of Aragon. Alphonsus was first performed in 1587 or 1588 and published in 1599 (DEEP). James Bednarz describes Greene’s rivalry with Marlowe, describing Alphonsus as an attempt to write a “morally acceptable alternative” to Tamburlaine (97; see also Ide). Bednarz suggests that “it is likely that the failure of Alphonsus, King of Aragon, [Greene’s] answer to Tamburlaine, caused him to temporarily retreat into print, after which he ultimately abandoned romance” (95). Ide suggests that Greene’s criticism of Tamburlaine was as much about “the failure of Alphonsus and his envy” as it was about “defin[ing] himself as a didactic, edifying playwright” in contradistinction to Marlowe (280).

After suggesting that Marlowe and the other “Gentleman poet” “hath sweat out all the greatest parts of their wits,” Greene asks his reader not to take offense at his insults and positions his attack as self-defense, writing, “I but answer in print, what they have offered on the Stage.” Rutter suggests that this “appears to indicate that Greene had been satirized in a lost collaborative play” (109). The defamatory play Greene references is sometimes considered to be “the mad priest of the sun,” which, as Roslyn Knutson documents, some critics read as a reference to the lost play Heliogabalus. Martin Wiggins and Catherine Richardson outline three possible interpretations of Greene’s words: a) Greene references “two Gentlemen poets,” listing one play by each poet; b) “Greene mentions two plays on which the two poets collaborated, in which case Marlowe may have written some or all of this play (and may therefore have had a collaborator on Tamburlaine, perhaps the author of the comic scenes which the printer claimed to have cut)”; and c) “the mad priest of the sun” is a play “in the same style as Tamburlaine, but Greene’s reference has no bearing on its authorship” (entry 786). Rutter contends that whether or not Greene is referencing a lost play, he elliptically invokes Heliogabalus as a “code for sexual irregularity” (115) in order to imply and disparage Marlowe’s homosexuality.

The title page of Perimedes the Blacksmith presents it as a didactic text offering exempla to be imitated: “A golden method, how to use the mind in pleasant and profitable exercise: Wherein is contained special principles fit for the highest to imitate, and the meanest to put in practice.” Greene envisioned a wide audience for his readership, from the highest class to the lowest; as he writes in his dedication to Gervase Clifton, he published this book with the classical Horatian goals to “profit” and “please” his readers. While we do not have any evidence about the early reception history of Perimedes the Blacksmith, we can only assume that Greene would be sour to learn that his book is remembered today only because he wrote about Christopher Marlowe.

Laura Estill, St. Francis Xavier University

Works Cited

Bednarz, James P. “Marlowe and the English Literary Scene.” The Cambridge Companion to Christopher Marlowe, edited by Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 90–105.

Bevington, David, and Eric Rasmussen, editors. Doctor Faustus and Other Plays. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Bull, Peter. “Tired with a Peacock’s Tail: All Eyes on the Upstart Crow.” English Studies, vol. 101, no. 3, Apr. 2020, pp. 284–311.

Downie, J. A. “Marlowe: Facts and Fictions.” Constructing Christopher Marlowe, edited by J. A. Downie and J. T. Parnell, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 13–29.

Erne, Lukas. “Biography, Mythography, and Criticism: The Life and Works of Christopher Marlowe.” Modern Philology, vol. 103, no. 1, Aug. 2005, pp. 28–50.

Hansen, Adam. “Marlowe and the Critics.” Christopher Marlowe in Context, edited by Emily C. Bartels and Emma Smith, Cambridge University Press, 2013, pp. 346–56.

Knutson, Roslyn. “Heliogabalus.” Lost Plays Database.

Kuriyama, Constance Brown. Christopher Marlowe: A Renaissance Life. Cornell University Press, 2002.

Ide, Arata. Localizing Christopher Marlowe: His Life, Plays and Mythology, 1575-1593. Boydell & Brewer, 2023.

Martin, Mathew R., ed. Tamburlaine the Great: Part One and Part Two. Broadview Press, 2014.

Ribner, Irving. “Greene’s Attack on Marlowe: Some Light on ‘Alphonsus’ and ‘Selimus.’” Studies in Philology, vol. 52, no. 2, 1955, pp. 162–71.

Rutter, Tom. “Marlowe, the ‘Mad Priest of the Sun’, and Heliogabalus.” Early Theatre, vol. 13, no. 1, 2010, pp. 109–19.

Syme, Holger Schott. “Marlowe in His Moment.” Christopher Marlowe in Context, edited by Emily C. Bartels and Emma Smith, Cambridge University Press, 2013, pp. 275–84.

Wiggins, Martin, with Catherine Richardson. “786: Play of a Mad Priest.” British Drama 1533–1642: A Catalogue, Vol. 3: 1590–1597. Oxford University Press, 2013.